In 1979, as a freshman in high school, I read a book by Ralph Ellison that by title alone described precisely how I felt as ninth grader – Invisible Man. I was fourteen, trying to find my way as a young man so I sort of understood why people did not recognize me as a man. Still, I was perplexed by the feeling of invisibility.

Routinely, I would pinch myself and look into the mirror to make sure that I wasn’t hallucinating. I wanted to be certain that I was a real person. With each painful pinch and long stare, I was convinced that I did in fact exist. Neither the propensity of my stares nor the intensity of my pinches seemed to matter. The upper-class students never acknowledged me, the freshman girls who liked me only months before ignored me, and teachers spoke at me not to me.

1ST SEMESTER FRESHMAN ENGLISH

One day in English class, Ms. Griffin – of course, not speaking to me but at me – assigned the Invisible Man for the entire class to read. Looking at the title, I initially thought it was some Sci-Fi book about a man who could choose to be invisible whenever he wanted.

As an unnoticed young man, it probably goes without saying that I thought being invisible upon one’s choosing was the coolest thing ever. I contemplated what I would do if I had superhero type invisible powers. I envisioned enacting revenge on all those who were ignoring me and best of all they wouldn’t have a clue that it was me who was haunting them.

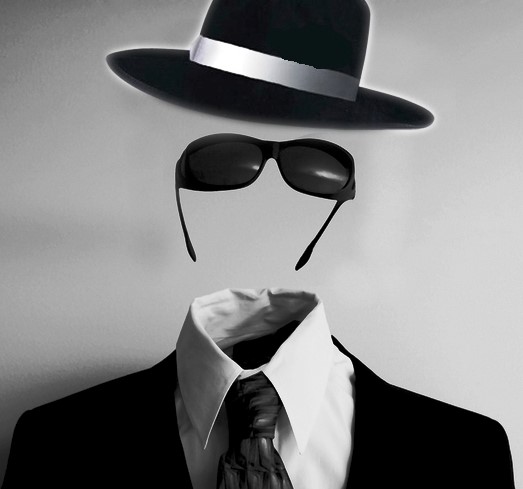

Imagine my surprise, once I started reading the book. Invisible Man wasn’t a book about a man with invisible powers. Rather, Invisible Man was a book about me, a man who wanted to be visible but others choose to deny his existence. Thirty-five years later those feelings from my freshman year in high school have returned and they’ve returned with a vengeance.

STILL AN INVISIBLE MAN

Let me first state that this isn’t the first time, I’ve felt like the “Invisible Man” over the past thirty-five years. There have been recurrent invisible moments on a nearly daily basis. From times when I’ve walked into a car dealership and no one asks if I need assistance. The occasions where I’ve attempted to hail a taxi only to be hastily passed. To times where I’ve walked into boutique clothing stores to purchase something for my family and not one clerk even pretends to be interested in helping me. Let’s not forget the typical failure to hear “thank you” after holding the door or extending some other common courtesy for a fellow human being.

Yet, these invisible moments are but a trifle compared to the present feelings of invisibility. What I feel today profoundly trumps what I felt as a ninth grader. What I feel today is Invisibility 2.0. Today my feelings of invisibility are derived from the fact that the thing that I hold dearest, the one thing I know that I do as well if not better than all others on the planet is consistently ignored by those who have the power to shape the thoughts and ideas of a community and more importantly the perceptions and opinions of society at large.

I AM A DAD

I am a dad but I’m not just any dad. I’m a great dad! While my words, on the surface, may appear braggadocios, I can assure you that these are not the words of a braggart. These are the words that anyone who knows me and has ever met my son use to describe me. These are the words of a man who has up close and personal experience of what it means to be raised by an average to below average dad.

My words are those of a man who knows what it’s like to grow up in one of the worst urban areas in America with little hope and even fewer expectations. My words are spoken from a lineage of absent, cold-hearted, and disconnected fathers. My words are words from a man who has spent the bulk of his life studying and observing those men who see being a dad as a profession. My words are those of a man who made it his life purpose to be one of the all-time great dads.

Yet, no matter where I turn rarely are great dads like me made to feel anything other than invisible. Turn on the TV, open a magazine, search the internet, and dads like me are inconspicuously absent. Did I mention that I am an African American dad who is not a professional athlete, an actor, or an entertainer? Did I mention that I can’t dunk a basketball, that I don’t run fast, that I have yet to make it to the big screen, and that I only sing in the shower?

I WENT PRO IN SOMETHING OTHER THAN SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT

You will never see me kissing The Vince Lombardi Trophy but you will find me showing my son affection every day of his life. You will never see me embracing The Larry O’Brien NBA Championship Trophy but you will see me embracing my responsibility to be my son’s copilot to help him navigate life at every turn. You will never find me chastising someone while presenting a Grammy Award but you will find me presenting my son with hot cooked meals that I prepared from scratch, freshly laundered clothing that I washed and dried myself, and a place to lay his head comfortably every night where I am before he closes his eyes and after he awakes each morning. And odds are that you will never find me dressed in formal attire sitting at a table waiting with slim to no chance of hearing my name called by the Academy but you will find me sitting at the kitchen table helping him with homework, seated at all parent-teacher conferences, and sitting in the stands of every academic, sporting, and extracurricular event.

Amazingly, despite my professional performance, I am not the dad that is written about profusely. Nor am I the dad who is featured in television advertisements, and celebrated on magazine covers. Ironically, I am the dad that provides the greatest likelihood that those consistently denigrated as being absent and deadbeat can most easily imitate. If society truly cared, I am the dad whose own story of commitment and persistence could be a model to change the perspectives and attitudes held by and about African American fathers.

VISIBLE ME

My examples of manhood and fatherhood could be a game changer because what I’ve done and what I continue to do as a dad is easily attainable. To model me doesn’t require an attempt to reach the formidable and burdensome economic comparisons placed upon men who will never win a Super bowl, be an NBA champion, sellout an international concert tour, or star in a blockbuster movie.

My example of manhood and fatherhood are free from commingling the words “father”, “annual income” and “net worth”. To model what “Invisible Men” like me are doing would allow any man the ability to embrace fatherhood free of the latent and long-established male disillusionment of not being amongst the rich and famous.

The chances one will be a professional athlete or entertainer no matter the amount of effort or relentlessness of their commitment are infinitesimal. However, the chances one can be a great dad is 100% if you give maximal effort, have a process, and are totally committed. My life and other “Invisible Men” who are great dads is proof that this can be done.

TAKE ME AS AN EXAMPLE

All I have done is raise a man – to name a few of the many noteworthy things – who considers education to be priceless, who cares authentically about his fellow person, who is multilingual, who traveled and lived abroad, who has authored a book, who has been featured in national publications, who is excelling as a STEM major, who is preparing to begin a PhD in STEM, who started a foundation, who is driven by his own mission statement, who is an entrepreneur, who is gainfully employed, who holds several service positions at his university, who is an entrepreneur, and who above all believes he is responsible for leaving the world in better condition than it was when he arrived.

Despite, the sacrifices I made to be home every day, to forgo more lucrative professional opportunities, and to place my wants secondary so that my son would never be amongst the growing despicable statistics of children raised in homes without fathers, children who receive no financial assistance from their father, and children who do not know their fathers, I just like so many other African-American fathers remain an “Invisible Man”. Out of curiosity, I’d like to know how many times have you seen me or heard me discussed during today’s Father’s Day celebration?

CAN YOU SEE ME

On Mother’s Day 1998, my family and I were preparing to record a video to celebrate my mom. Just before we started to record, my then two-year-old son – as small children are apt to do – decided this was a great time to play hide and seek. While hiding, while seeking to be undetectable, my son asked me this question “can you see me, daddy?”

Today, as I once again pinch myself and stare into the mirror, I ponder similar thoughts not about my high school but about America. America can you see my son’s daddy on Father’s Day? Do you want to see my son’s daddy on Father’s Day or any other day? Or is it preferable like it was for me in the ninth grade that those who have the power to acknowledge me prefer that I remain an “Invisible Man”?

How many regular African American father’s did you see featured in advertisements this Father’s Day? Do you believe positive fathers of color (outside of athletes and entertainers) are represented equally? Are the media’s images and portrayals of great fathers diverse and inclusive?

The dearth of African American fathers in today’s mainstream Father’s Day advertisements and the limited national dialogue about engaged African American fathers is why I decided to reshare this post. The following article originally appeared at The Good Men Project.

[…] a product of one of Americas most segregated, economically depleted, and socially challenged cities, I’m further troubled by the perpetual […]